Chinatown Gate

Surface Road x. Beach St.

Called a paifang, the gate to Boston’s Chinatown was donated by the Taiwanese government in 1982. Compact yet bursting with bakeries, restaurants, and small grocers, Chinatown is a banquet for the senses. The gate marks the official entry point to the district and is flanked by the Rose Kennedy bamboo park on Surface Road. Thanks to community land developers, the plaza in front of the gate now hosts a playground and public seating.

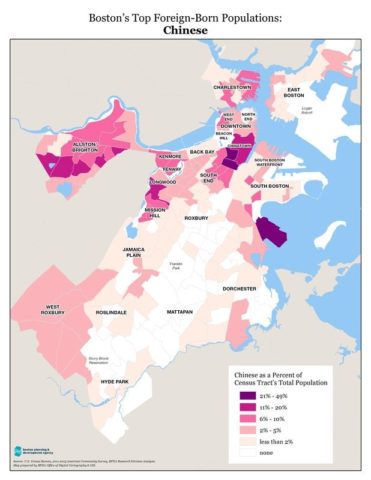

Chinese

Chinese Overview

The oldest group in this gallery, Chinese-Bostonians share a deep connection to the heart of old Boston, and today’s Chinatown is a symbol of a rapidly changing, deceptively diverse fusion of old and new.

Sacrificial offerings cover this altar at the Chinese immigrants’ memorial in Mt. Hope Cemetery. Descendants believe their ancestors will receive food and drinks placed here, which include Coca-Cola, stacks of oranges, a bottle of cooking wine, and—perhaps fittingly for Boston—two cans of Guinness. A lighter is left for others to light incense and candles.

“A Bachelors’ Society”

Chinese immigrants first migrated to the U.S. en masse during the California gold rush, composed of young unmarried men who worked contracts for mining and railroad companies. They came from Taishan, an impoverished region of Southern China. Gradually, they trickled eastward from California as anti-Chinese labor laws reduced job opportunities in the 1860s and 70s. Coming by way of transcontinental railroads, the first settlers in Massachusetts arrived as strikebreakers. In Boston, they settled in the South Cove landfill, an immigrant enclave where Syrians, Irish, Italians, and other immigrants were relegated.

Exclusion and Expulsion

The passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and further anti-immigration sentiment threatened to kill off Boston’s Chinatown. Immigration raids and efforts by the city to demolish impoverished areas convinced many to leave. Nevertheless, many Chinese settlers began making Boston their permanent home. Excluded from practically all jobs, Boston’s Chinese began setting up their own businesses, mostly laundries and later restaurants. In 1903, an infamous immigration raid conducted by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts arrested over 250 residents, and subsequent fears of deportation cut down Chinatown’s population by half. City officials characterized Chinatown as filthy, poor, brimming with opium and gang violence, and arrested anyone who did not have immigration papers on hand.

Culture and Community

As Chinatown solidified its presence, internal groups began weaving the framework of a community. At first, tongs, secret mafia-like gangs, organized opium dens, gambling rings, and extortion rackets across Chinatown. Occasional bouts of violence between rival tongs gave Chinatown an infamous image in the press, and disdain among the city police. Yet tong influence gradually waned through the 1910s, and Chinatown became more hospitable for families and businesses. Civic leaders built community schools and mutual aid organizations, many of which still stand today at the tail end of a century. Family associations, with membership based on common surnames like Wong and Chin, acted as fraternal associations that provided brotherhood among a mostly male population. External support from Christian missions and settlement houses provided community support and helped set up American institutions like the Chinatown YMCA, Boy and Girl Scout Troops, and Christian churches. .

Women of Chinatown

The “bachelors’ society” of Chinatown began to change in the early 1900s, despite the official exclusion of all Chinese immigration until 1943. As ethnic cleansing (ranging from local anti-Chinese labor laws to massacres of laborers) drove Chinese immigrants out of Western states, more families settled in Boston. San Francisco’s 1906 earthquake destroyed immigration records, enabling thousands of Chinese immigrants to claim citizenship and bring their wives and children into the country. Bribery and falsified documents enabled Chinese women to come to Boston via the Canadian border. In the 1930s, Chinese women formed the New England Chinese Women’s Association, actively campaigning for Chinese nationalist causes and the end of Japanese occupation of China. Amelia Earhart led women’s programs at the Denison House in Chinatown in the late 1920’s. Five years after she left Boston, 18-year-old Chinatown native Rose Lok flew solo from Logan Airport as one of the first Chinese female pilots in history.

“Urban Renewal”

“Death, disease, poverty, and loneliness:” Even before City Hall’s 1956 Urban Renewal plan called for the destruction of 90% of Chinatown’s residential space, Boston’s government had been trying to clear the “filth” for half a decade. The widening of Harrison Avenue in 1893 was a first attempt to drive out residents; the noise and pollution brought by the elevated “El” tram in 1900 drove out everyone except the Chinese. By the 1960s, construction of the Massachusetts Turnpike and expansion of Tufts Medical Center had reduced Chinatown’s land base by half and displaced hundreds of families. Boston’s adult entertainment district moved adjacent to Chinatown with Boston City Council approval in the 1960’s. It separated Chinatown from Boston with a “Combat Zone:” an industry of adult films, brothels, and prostitution. After advocacy by Chinese civic leaders and local families to eliminate the area and economic changes, Chinese and Vietnamese business owners established themselves in this area during the 1980’s.

Like most Chinatowns across the country, Boston’s Chinatown is facing rapid gentrification and redevelopment. The number of luxury apartments in the area tripled in 2013, and today less than half of the district’s residents are ethnically Asian. The work of local nonprofits, including business associations and land trusts, has been vital in creating income-restricted housing for new Asian immigrants and reaffirming Chinatown’s heritage and roots through artistry and engagement.

Modern Chinatown

Today, the Chinatown of 2020 is as dynamic as the rest of Boston. Chinese immigrants still struggle with a feeling of invisibility within America’s strict racial framework, and urban redevelopment frequently threatens Chinatown’s historic core. Younger Chinese residents have moved to the suburbs and Chinatown is increasingly diverse. New waves of Vietnamese, Korean, Thai, Cambodian, and southeast Asian immigrants have settled in Chinatown. New tea shops and cafes serve trendy fusion cuisine and milk tea in the shadow of restaurants half a century old. Chinatown is a touchstone for Boston’s wider Asian community, a place that has always been living history.

Community Spotlight

Please click on the map dots to learn more about each location. They represent many different aspects of the Chinese community. Each location contains a general description as well as additional photos and contact information.

-

-

Mount Hope Cemetery Chinese Burial Memorial

355 Walk Hill St., Mattapan, MA

Below tombstones resembling falling dominoes, the first members of Boston’s Chinese community are buried. Some 1500 graves, representing migrants born as early as the 1860s in Taishan, lie in dense formation at the very back of Mt. Hope Cemetery, one of Boston’s oldest public burial grounds. In 1989, a group of Chinatown community members began the work of restoring and rediscovering the history and genealogy of those buried here, ultimately founding the Chinese Historical Society of New England to continue their mission. In 2007, a memorial funded by their efforts was erected at the site, paying long-awaited homage to those pioneers with carved words written in calligraphy: “Remember those who came before you” and “Long rivers flow from distant origins.” -

Old Rose Lok House and Denison Settlement at 93 Tyler St.

The Denison Settlement House was located here until WWII, where it offered a variety of services to the immigrants of South Cove, predominantly Syrians and Chinese. Entirely led and run by women, Denison offered a safe space for immigrant women to care for children, learn English, and play sports. In the late 1920s, Amelia Earhart led the Syrian Mother’s Club and coached girls’ sports at the settlement house, taking the weekends off to fly. Growing up next to the Denison House, Rose Lok perhaps saw in Earhart a role model for her own dreams. Whether coincidence or not, she became a pilot herself at age 18—one of the first Chinese-American women to take to the skies, from Logan Airport. -

Asian Community Development Corporation

38 Oak Street, Boston, MA

617-482-2380

Boston’s Chinatown faces staggering levels of gentrification today. As more residents move out to more affordable neighborhoods like Quincy, Malden, and Brighton, the CDC has worked to create affordable housing in Chinatown and build parks and community spaces in the small district. Because of its work, parks and playgrounds have been reclaimed from vacant lots, and public murals have cropped up around Chinatown. -

Boston Chinatown Neighborhood Center

38 Ash Street, Boston, MA

617-635-5129

Founded in 1969 by a group of activists seeking to reform the local Josiah Quincy School, the BCNC has become one of the largest nonprofits in Chinatown. Nowadays, its work supports many Asian immigrant groups in Boston and Quincy, funding adult education and youth enrichment programs. In 2017, the BCNC partnered with the Bunker Hill Community College to build the Pao Arts Center in Chinatown, an effort to promote creative and cultural arts among the Asian community.

Themes

- Guangdong Province, beset by Taiping Rebellion and famines in the 1850s, sends young men to California in search of gold and jobs

- First trickle of immigrants came by way of California as strikebreakers to North Adams, MA

- Others were upper class students and “curiosities,” owning exotic tea shops

- First settlers in Boston make homes in South Cove, a landfill and immigrant enclave

- 1903 immigration raid reduces Chinatown’s population by half, nearly marking the end of the district

- 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act motivated many further immigration raids

- City infrastructure and planning become a constant antagonist of the community

- 1893 widening of Harrison Ave threatens businesses

- Tram railways of the early 1900s create noise and pollution

- Successful businesses catalyze growth of Chinatown from 1900-1930

- Laundries and restaurants open an economic niche for settlers

- Internal groups begin to emerge, creating cultural infrastructure

- Tongs (family clans) first emerge as drug dens and gambling rings

- Community advocates establish benevolent associations and merchants’ clubs in 1920s

- Family associations unite early settlers, mostly men, with the same surname in fraternal clubs

- Political activism and nationalism characterize WWII years

- New England Chinese Women’s Association (NECWA)raises money and advocates against the Japanese occupation of China

- Construction of the first major highways (MA Turnpike and Artery) threaten to destroy Chinatown

- Tufts and NEMC in 1970s encroach greatly upon Chinatown’s borders

- “Combat Zone” 1960s-1980s along Washington St. separates Chinatown from Downtown Boston with adult entertainment district

- Modern Chinatown faces challenges and new diversity

- Land trusts and community organizations work to increase affordable housing

- A new generation of businesses, including milk tea cafes and restaurants

- New Southeast and East Asian immigrant groups settle, adding incredible diversity

77k

Chinese Americans in Greater Boston with 30k in Boston

1st

largest immigrant group in Greater Boston, while Massachuestts holds the 4th largest Chinese population in the US

$79k

is the median income for Chinese living in Greater Boston while 30% of foreign-born Chinese live in poverty

22%

of Chinese Bostonians are homeowners